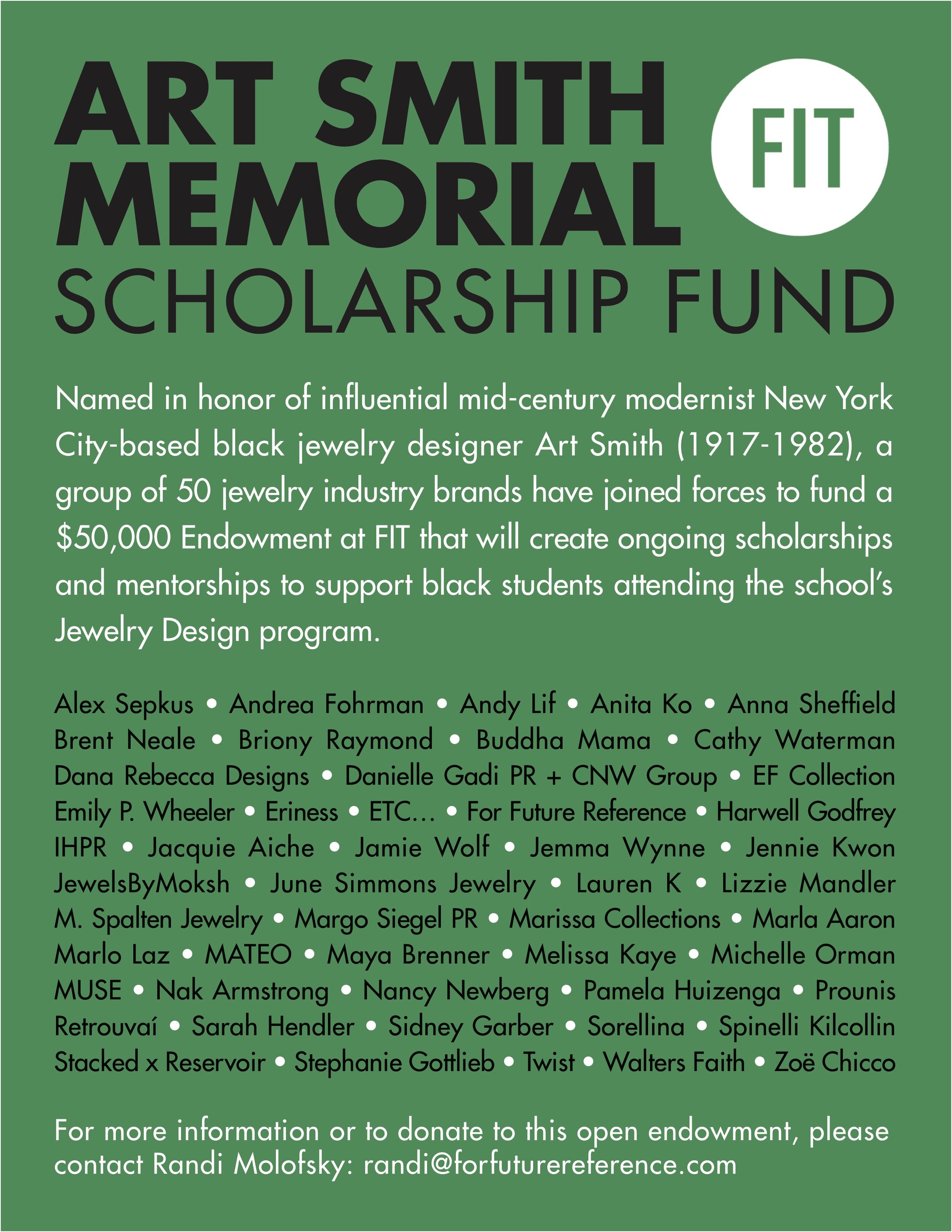

For Future Reference and Brent Neale are proud to announce The Art Smith Memorial Scholarship Foundation. Named in honor of influential mid-century modernist New York City-based black jewelry designer Art Smith, a group of 50 jewelry industry brands joined forces to fund a $50,000 Endowment at FIT that will create ongoing scholarships and mentorships to support black students attending the Jewelry Design program. People of color are historically underrepresented in the jewelry industry and our goal is to turn that statistic around, with your help, one student at a time.

We stand with the Black community and with all victims of racism. We will continue investing our time, energy and resources to support communities that have been historically marginalized, and we will increase our efforts to fight for the systemic changes that are so urgently needed.

The Endowment is now open for donations of any amount and is classified as a 501(c)3. Please click the link below to become a FIT donor and make a difference in the lives of future jewelry design students.

ABOUT ART SMITH

Arthur George “Art” Smith (1917-1982) was an influential mid-century modernist jewelry designer. He created wearable sculpture that adorned the bodies of modern dancers and famous clients like Duke and Ruth Ellington. Influenced by Surrealism and African motifs, Smith’s silver, brass, and copper jewelry embrace their three-dimensionality, creating unique geometric shapes. Smith was highly attentive to how jewelry interacts with the human body, and often incorporated biomorphic shapes into his work – that is, shapes that recall living organisms.

Arthur Smith was born to Jamaican parents in Cuba in 1917. His family settled in Brooklyn in 1920 and Smith showed artistic talent at an early age, winning honorable mention as an eighth grader in a poster contest held by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Encouraged to apply to art school, he received a scholarship to Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. There he was one of only a handful of black students, and his advisors tried to steer him towards architecture, suggesting he might readily find a job in the civil sector of that profession. His lack of proclivity for mathematics eventually forced him to abandon this path, however, and he turned to commercial art and a major in sculpture, training that would prove invaluable.

After graduating in 1940, Smith worked first with the National Youth Administration and later for Junior Achievement, an organization devoted to helping teenagers find employment. He also took a night course in jewelry making at New York University. That and the friendship with Winifred Mason, a black jewelry designer who became his mentor, set him on the course of his adult artistic life. Mason had a small jewelry studio and store in Greenwich Village, and Smith became her full time assistant. He subsequently moved from Brooklyn to the Village’s Bank Street. In 1946 Smith opened his own studio and shop on Cornelia Street in the village with the financial assistance of a near-stranger who wished to undermine Mason because of bad feelings over business transactions. Cornelia Street was an “Italian block” then, and Smith suffered racial violence from some of his neighbors. His store-front windows were smashed on one occasion and he was made to feel dangerously unwanted. Soon after, he moved to 140 West Fourth Street just 1/2 block from Washington Square park, the heart of Greenwich Village where as an openly gay black artist he felt more at home.The new store was better located business-wise and socially, and Smith’s career began to take off.

In addition to selling from this new location, he started to sell his wares to craft stores in Boston, San Francisco, and Chicago, and by the mid-1950s he had business relationships with Bloomingdale’s and Milton Heffing in Manhattan, James Boutique in Houston, L’Unique in Minneapolis, and Black Tulip in Dallas. An important early influence on Smith’s career was Tally Beatty, a young black dancer and choreographer. Beatty introduced Smith to the dance world “salon” of Frank and Dorcas Neal, where he became acquainted with some of the city’s leading black artists including writer James Baldwin, composer and pianist Billy Strayhorn, singers Lena Horne and Harry Belfonte, actor Brock Peters, and expressionist painter Charles Sebree. Through Beatty, Smith also began to design jewelry for several avant-garde black dance companies, including, in addition to Beatty’s own, those of Pearl Primus and Claude Marchant. These commissions encouraged him to design on a grander scale than he might otherwise have done, and the theatricality of many of his larger pieces may well reflect this experience.

In the early 1950s Smith received feature pictorial coverage in both Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar and was also mentioned in The New Yorker shopper’s guide, “On the Avenue.” For many years thereafter he ran a small advertisement in the back of The New Yorker. By the 1960s he had begun to use silver more readily in his jewelry, and as his client base increased so did his custom designs. He received a prestigious commission from the Peekskill, New York, chapter of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People, for example, to design a brooch for Eleanor Roosevelt, and he made cufflinks for Duke Ellington that incorporated the first notes of Ellington’s famous 1930 song “Mood Indigo.” In 1969 he was honored with a one-man exhibition at New York’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Art and Design), and in 1970 he was included in Objects: USA, a large traveling exhibition organized by Lee Nordness, an influential early dealer in craft objects.

After his death 3 major exhibits were organized celebrating his work; "Arthur Smith A Jeweler's Retrospective" at the Jamacia Arts Center in Queens NY, 1990, "Sculpture to Wear; Art Smith and his Contemporaries", at the Gansevoort Gallery, NYC, 1998, and "From the Village to Vogue" at the Brooklyn Museum., 2008. Small catalogues from the 2 museum shows are available. The definitive collection and exhibit of all the artist jewelers of Art Smith's generation is beautifully illustrated and discussed in "Messengers on Modernism American Studio Jewelry 1940-1960", written by Toni Greenbaum published by Flammarion and the Montreal Museum in 1996. Smith had had a heart attack in the 1960s, and by the late 1970s his health had declined. The shop on West Fourth was closed in 1979 and Art Smith died in 1982.